Open call for artist-in-residence proposals, in partnership with the CAMAC contemporary art centre of Marnay-sur-Seine

Launch of the call for residency applications, in May 2017

Upcoming – Launch of the call for residency applications, in May 2017

The Musée Camille Claudel (Nogent-sur-Seine) and CAMAC (Marnay-sur-Seine) will launch a joint call for artist-in-residence proposals in May 2017. This artist-in-residence programme is meant to encourage artistic creation, while promoting exchanges and dialogue between the invited artist and visitors to the CAMAC contemporary art centre and the Musée Camille Claudel. This first call for proposals will invite an artist-choreographer to offer his/her critical perspective on both the collections and sculptural creation.

Entrevus-Camille

Hands-on workshop

Sign up now for “Entrevus-Camille”, a hands-on corporeal mime workshop hosted by the Compagnie Hippocampe.

Information and reservations: +33 (0)3 25 24 76 34

Practical information

Place :Auditorium

Musée Camille Claudel

10 Rue Gustave-Flaubert

10400 Nogent-sur-Seine

Hands-on workshop

Entrevus-Camille

Sign up now for “Entrevus-Camille”, a hands-on corporeal mime workshop hosted by the Compagnie Hippocampe.

Group composition of a short performance based on sculptures by Camille Claudel, to be presented during the European Museums Night on 20 May 2017 at the Musée Camille Claudel in Nogent-sur-Seine.

We invite you to participate in this group experiment drawing inspiration from Camille Claudel's oeuvre to create a collective composition. Together explore the foundations of a unique creative process, the dramatic art of which will initially rely on movement.

The workshops will focus on various mime techniques: body segmentations, dynamo-rhythms and causalities, as well as figures drawn from the corporeal mime repertoire. The goal is to learn how to articulate movement, to lend it a certain dynamic quality, and to develop one’s stage presence.

Luis Torreão

Director, actor and corporeal mime instructor. State-certified drama teacher. Director of the Compagnie Hippocampe and its school. Studied corporeal mime in Paris and in the United States under Thomas Leabhart, working as his assistant from 1997 to 2003.

His dramatic creations include: Les Collectionneurs, La chambre de Camille, Labyrinthe 1, Of Men and Women and Traçado. Since 2000, he has taught corporeal mime at the Hippocampe in Paris and has led numerous training courses in France and Brazil.

Opening

Creation by the compagnie Joëlle Bouvier

To mark the opening of the Musée Camille Claudel on 26 March 2017, the Compagnie Joëlle Bouvier presents a performance echoing the oeuvre and creativity of Camille Claudel, inspired by the “sensuality”, “dizzying depth” and “fiery spirit” of her sculptures: “Rather than simply copying and setting them in motion, we will draw inspiration from the world conjured by these sculptures. The Gossips, Crouching Woman, The Abandonment, The Mature Age, Dream by the Fire… all of these bodies – full of ardent love, desire, solitude, compassion, heaviness, infinite sweetness or astounding fervour – will serve as guides in our creating a choreography that also evokes Camille Claudel the woman.” (Joëlle Bouvier)

In 1980, Joëlle Bouvier created the ESQUISSE company, in collaboration with Régis Obadia. She has co-produced 15 choreographic works performed around the world and co-directed 4 short films awarded prizes at numerous festivals (Official Selection at the Cannes Film Festival, FIPA d’Argent, Prix de la SACEM, etc.).

Her numerous creations include De l’Amour (2002), Le Voyage d’Orphée (2004), Face à face, La Divine Comédie (2006) and Ce que la nuit raconte au jour (2008).

She was awarded the critics’ grand prize for Tristan & Isolde, Salue pour moi le monde !, set to the music of Richard Wagner, voted best performance of the 2015/2016 season.

Visitors trails

Sculpture in middle-class homes

After the fashion of the mechanically reproduced prints popular during the 19th century, reproductions of sculptures abundantly adorned middle-class interiors. Reproductions were produced to suit all budgets (in bronze, patinated plaster, Sèvres bisque porcelain, carton-pierre, zinc plated in copper via galvanoplasty, etc.), as well as all tastes. Miniatures in different sizes were also made available.

The boom in the production of bronzes during the 19th century was made possible thanks to three innovations. Firstly, the device invented by Achille Collas, which allowed its users to mechanically reduce or increase the scale of models. Achille Collas was awarded a Grand Médaille d'Honneur for his invention at the 1855 Exposition Universelle of Paris. Secondly, progress made in the sand casting technique, which allowed for the mass reproduction of a given work. Thirdly, the establishment of contracts between sculptors and foundries, which protected the creators’ ownership rights and ensured them an income. The manufacturers’ success depended not only upon technical advances, but also their marketing talents and their discernment in the selection of artists and oeuvres likely to satisfy the dominant academic tastes of their middle-class clientele. No less than 153 manufacturers were present at the Exposition Universelle of 1889. Among this multitude, a few names stood out, with their boutiques resembling art galleries: Barbedienne, Susse Frères, Thiébaud Frères, Siot Decaux-Ville and Hébrard. Bronze reproductions were a hallmark of the 19th century, embodying the century’s dream: the marriage of art and industry, backed by the French state both for economic reasons and as a means of supporting France's image as a nation of the arts.

19th-century sculpture was marked by the manufacture of reduced scale reproductions. In the 1870s and 1880s, contemporary works became increasingly common in the manufacturers’ catalogues. Numerous artists created works destined specifically for industrial production. At the same time, monumental works commissioned for the public sphere, such as funereal sculptures, were added to the catalogues. This trend was illustrated, for example, by The Spinner of Bou-Saada created by Barrias for the tomb of the painter Guillaumet at the Montmartre cemetery.

Among the most fashionable subjects were historical themes, female nudes tinged with eroticism and the figures of children. Sculptors did not hesitate to place their talents at the service of the decorative arts, notably in the designing of vases (Cheret, Rodin, Desbois, Dalou, etc.) and spectacular centrepieces (Frémiet and Agathon Léonard).

Sculpture of Camille Claudel's time

The Nogent-sur-Seine collection stands out for its temporal coherence, presenting sculptures from approximately 1870 to 1910, a particularly splendid period for sculpture and especially rich starting in 1880 with the nascent stylistic transformation characterized by a search for expression and meaning.

The section “Sculpture at the time of Camille Claudel” considers how sculptors – attached to the subject and the body's representation, steeped in classical culture and technically impeccable – positioned themselves during this period of transformation, borrowing from various sensibilities according to the subject, or on the contrary limiting themselves to a constant, personal search for expressiveness and meaning.

What is the significance of this profusion of sculptures in the public sphere, commissioned by the triumphant French Republic or groups of citizens seeking to pay tribute to their “great men”? This sculpture of the street, the "people's museum", tells a story, instructs, moralizes and adorns. How are mythological subjects interpreted in the academic and symbolist milieus? What is the influence of the rediscovery of the Florentine Quattrocento? Given the confusion of styles present during this period, and the scientific studies in anatomy and morphology taught at the École des Beaux-Arts fine arts school, what canons of the nude female body were adopted? How did this young democracy present the image of “work”? What subjects best evoked this “movement” that so well symbolized the 19th century?

A projection room allows visitors to immerse themselves in the Paris and the Parisian art life of the late 19th century familiar to Camille Claudel.

One at once understands the extent to which, in this context, competition was fierce, especially for a young female sculptor, whose first obstacle was locating a school welcoming women, and then managing to stand out amongst the plethora of sculptors present at the annual Salon, affirming her originality and seeking understanding. While the evolutions in painting during this period – notably impressionism – are well known, those in sculpture are yet to be fully explored. Camille Claudel belongs to the movement initiated principally by Rodin. The contextualization of her creations is therefore all the more rich in meaning.

sculpture in middle-class homes

Museum of sculpture

By the quirks of fate, four sculptors, renowned during their lifetime, have resided in Nogent-sur-Seine: Marius Ramus (1805-1888), Paul Dubois (1829-1905), Alfred Boucher (1850-1934) and Camille Claudel (1864-1943). They maintained intergenerational professional relations and held each other in friendly esteem. The museum of Nogent-sur-Seine, created under the impetus of Alfred Boucher, today presents an important collection of sculptures by these four artists, further enriched by numerous works created by their compatriots.

At the height of his success, Alfred Boucher strove to found in Nogent-sur-Seine the museum that had been lacking during his own apprenticeship under Marius Ramus. This philanthropist drew largely from his own personal collection and solicited his friends and acquaintances, while the town acquired the so-called “Château” to house the new museum. The children of Marius Ramus and Paul Dubois also lent their support to the project.

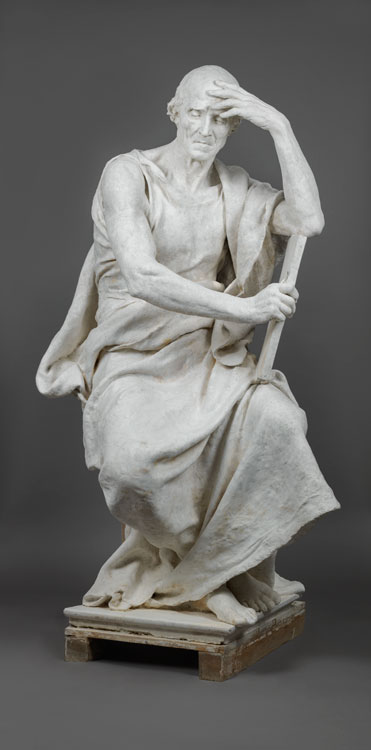

The Dubois-Boucher Municipal Museum was inaugurated on 12 October 1902. On 21 May 1905, the sculpture gallery, housing primarily large-scale models destined for the public sphere, was in turn inaugurated, thanks to the generous contributions of Alfred Boucher’s friends and the widow of Paul Dubois. The museum was therefore capable of welcoming the full-scale model for the Joan of Arc equestrian statue by Paul Dubois the very day of the museum’s 1902 inauguration ceremony. The museum continued to strengthen its specificity: sculpture from 1870 to 1910. Studio collection donations contributed to the creation of a museum of sculpture and of sculptors. This particularity would be further reinforced by the coherent acquisition policy pursued between 1980 and 2013, peaking with the purchase of works by Camille Claudel from Reine-Marie Paris and Philippe Cressent in 2008. The same year, the town managed to purchase the only monumental marble work by the artist, thanks to the contributions of patrons and the Fonds du Patrimoine national heritage fund (attributed by the French Ministry of Culture).

The radical transformation of the municipal museum – involving the construction of a new 2,400-m2 building, as well as the renaming of the museum (the first in the world to be named after Camille Claudel) – has necessitated a reconsideration of its collection and the redesigning of its exhibition to put into perspective the oeuvre of Camille Claudel and examine the role she played in the artistic landscape of her period.

sculpture in Camille Claudel's time

Camille Claudel and Nogent-sur-Seine

It was in Nogent-sur-Seine that Camille Claudel’s lifetime calling as a sculptor first took shape. She was twelve when her father was named registrar of mortgages in the administrative capital of the Aube canton. Louis-Prosper Claudel would occupy this position from 1876 to 1879, three years that would leave their indelible mark on his eldest daughter. The young girl became fascinated by modelling.

In this pottery-making region, she found the clay she needed on-site. This activity became so important within the family home that the ever attentive father eventually decided to seek the advice of Alfred Boucher, awarded second prize in sculpture for the Prix de Rome bursary in 1876, most likely upon the artist’s return from Italy. Boucher regularly returned to Nogent to call on his parents. This meeting would prove decisive, with Alfred Boucher detecting the budding talent of the self-taught Camille Claudel. He set about teaching her the rudiments of sculpting, correcting and encouraging her and reinforcing her choices. He was convinced of her artistic qualities.

Alfred Boucher’s opinion undoubtedly played a central role in Louis-Prosper Claudel’s decision to send to Paris, in 1881, his wife, Louise Athanaïse Claudel, and their three children, Camille, Louise and Paul, so as to offer them a superior education. In Paris, Camille Claudel took courses at the Académie Colarossi, and shared a studio with young female English students. Alfred Boucher stopped by twice weekly to follow her progress, up until 1882 when a gold medal at the Salon des Artistes Français gave him the opportunity to pursue a study trip to Florence. But prior to departing, he convinced Auguste Rodin to take over for him. This choice was significant, for Alfred Boucher, who had orchestrated his defence during The Age of Bronze affair, considered Rodin the greatest sculptor of his time.

The acquisition in 2008 of the works by Camille Claudel collected by Reine-Marie Paris and Philippe Cressent, to enrich the museum created in Nogent-sur-Seine by Alfred Boucher back in 1902, can be seen as a second encounter between these two local artists.

1909-1943 : Period of confinement

Spells of delirious paranoia focusing on “Rodin’s band” influence her creative output, to the point of drying it up. She is confined to a mental hospital on 10 March 1913, where she will remain for the rest of her days.

Destructions

1911: Camille Claudel’s physical and mental health worsens, worrying her brother. She shuts herself in.

In a letter to Henriette Thierry (undated, circa 1912), she evokes her destructive tendencies:

“When I received your announcement, I was in such a state of anger that I took all of my wax models and threw them in the fire, it made quite a blaze and I warmed my feet in its glow, that’s what I do when something unpleasant happens to me, I take my hammer and smash up some chap […]

The large statue nearly met the same fate as its little wax sisters, for Henri’s death was followed a few days later by more bad news [...] And many more capital punishments were carried out soon after, with a pile of rubble accumulating in the middle of my studio, it's a veritable human sacrifice."

Correspondances, A. Rivière, B. Gaudichon, Paris 2008.

1913 : confinement

Camille Claudel is not informed of her father’s death on 3 March in Villeneuve-sur-Fère – the father who had ever shown his love for her and protected her. She would therefore not attend his funeral.

On 7 March, Doctor Michaux drafts the confinement certificate for Camille Claudel, who is now 48 years old.

On 10 March, she is confined at Ville-Evrard (in the Val-de-Marne). The procedure adopted is that of “voluntary placement”, as requested by her mother.

Montfavet

She is transferred to the Montdevergues asylum from 5-7 September 1914 due to the war. There she would remain until her death in 1943.

1929: Jessie Lipscomb and her husband visit Camille Claudel during a trip to Europe. This meeting is immortalized by a photograph.

Camille Claudel dies on 19 October 1943, at the age of seventy-eight. Her brother had last visited her on 21 September. She is first buried at the Montfavet cemetery in a temporary tomb, before being transferred to the communal grave.

Reconnaissance

In 1914, while Auguste Rodin is negotiating the establishment of his museum within the Hôtel Biron, on Rue de Varennes, Mathias Morhard requests that he set aside a room for Camille Claudel. Rodin approves the initiative, but Paul Claudel is categorically opposed. Rodin dies on 17 November. His funeral is held at the Villa des Brillants in Meudon, where he is buried.

Between 1934 and 1938, works by Camille Claudel are displayed at the Salon des Femmes Artistes Modernes (“Modern Women Artists Exhibition”).

In 1949, against all expectations, Paul Claudel requests that the Musée Rodin host a retrospective exhibition of his sister’s oeuvre. Cécile Goldsheinder and Paul Claudel work closely together, with the latter authoring the catalogue’s preface entitled “My Sister Camille”, in which he presents a study of her works and an intimate portrait of the artist.

In 1952, Paul Claudel makes an essential donation to the Musée Rodin: the first version of The Age of Maturity in plaster, the second in bronze, The Abandonment in marble and Clotho in plaster.